The poisoning plot seemed right out of a Russian playbook. An unhinged and vengeful chief of state, obsessed with historic grievances and destroying enemies. Obsequious apparatchiks slavishly devoted to following orders. Intelligence operatives trained in assassination techniques and eager to carry them out.

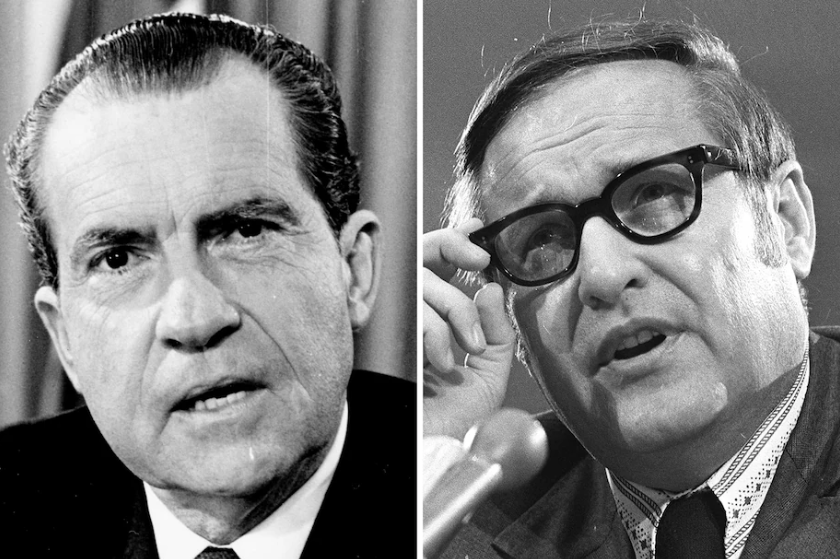

The Nixon White House plotted to assassinate a journalist 50 years ago

Nixon’s hatred for the news media long predated his election as president. Where other politicians shrugged off public criticism, Nixon believed he was uniquely the target of journalistic vilification. When he entered the White House in 1969, he vowed revenge.

The journalist Nixon despised most was crusading columnist Jack Anderson, then the most famous and feared investigative reporter in the country. Anderson had a hand in exposing virtually every Nixon scandal since he first entered politics, and he escalated his attacks once Nixon was president, uncovering Nixon’s deceit in foreign policy, and his political and personal corruption.

Nixon railed that “we’ve got to do something with this son of a bitch,” but nothing seemed to stop Anderson. The president’s reelection campaign planted a mole in the newsman’s office, but Anderson’s secretary discovered the snooping and ejected the infiltrator. A top White House adviser tried to discredit Anderson by leaking him forged documents, but he figured out they were bogus and didn’t fall for the ruse. The CIA illegally wiretapped and surveilled Anderson, but his nine children chased the spies away and Anderson mocked their incompetence in his column. The president even ordered his staff to smear Anderson as gay, but the allegation was as false as it was ridiculous and went nowhere.

Finally, in March 1972, the Nixon White House turned to the one method guaranteed to silence Anderson permanently: assassination. After meeting with the president in his hideaway office in the Old Executive Office Building, White House special counsel Charles Colson contacted his top White House operative, E. Howard Hunt. The “son of a bitch” Anderson “had become a great thorn in the side of the president,” Colson told Hunt, according to Hunt’s later Senate testimony, and the White House had to “stop Anderson at all costs.” (Hunt also corroborated this story to me in a 2003 interview.)

According to Hunt, Colson proposed assassinating Anderson by using an untraceable poison, perhaps a high dose of a hallucinogen like LSD. Colson instructed Hunt to “explore the matter with the CIA,” where Hunt had previously worked as a spy. Although he never explicitly stated that Nixon gave the order, Colson told Hunt that he was “authorized to do whatever was necessary” to eliminate the reporter.

Hunt brought in his White House sidekick, G. Gordon Liddy, who was “forever volunteering to rub people out,” as Hunt put it. Liddy was enthusiastic: It would be a “justifiable homicide,” he later said in media interviews, because Anderson was a “mutant” journalist who had “gone too far” and “had to be stopped.”

On March 24, 1972, Hunt and Liddy met with a veteran CIA poison expert, Edward T. Gunn, in the basement of the Hay-Adams Hotel, a block from the White House. Gunn and Liddy, who didn’t know each other, used aliases.

“Of course, there’s always the old simple method of simply dropping a pill in a guy’s cocktail,” Gunn suggested. But Hunt pointed out that as a Mormon, Anderson was a teetotaler.

“Aspirin roulette” was another option, Liddy said: slipping a “poisoned replica” of his headache tablet into his medicine bottle. Liddy and Hunt had already cased Anderson’s house for a possible break-in. But it would be “highly impractical,” Hunt argued, to “go clandestinely into a medicine cabinet with a household full of people and pore over all of the drugs … until you found the one that Jack Anderson normally administered to himself.”

Besides, Liddy realized, it would take too long: “Months could go by before [Anderson] swallowed it.” Not to mention the “danger than an innocent member of his family might take the pill” instead.

It might be simpler, Gunn suggested, to make Anderson’s car crash by ramming into it. Hunt and Liddy had already tailed Anderson as he drove between his home and office, and Gunn suggested a specific location along the route that was “ideal” because it was already “notorious as the scene of fatal auto accidents” in Washington.

But Liddy thought this method was “too chancy” and argued for simplicity: Anderson “should just become a fatal victim of the notorious Washington street-crime rate.” Liddy offered to stab Anderson to death and make it look like a routine robbery by stealing Anderson’s watch and wallet. “I know it violates the sensibilities of the innocent and tender-minded,” Liddy later told Playboy, “but in the real world, you sometimes have to employ extreme and extralegal methods to preserve the very system whose laws you’re violating.”

Hunt briefed Colson about these various assassination options. But a few days later, the hit was canceled. The White House had a more urgent assignment: bugging the Democratic Party’s headquarters in the Watergate office building.

A few weeks later, Hunt and Liddy were arrested for their role in the Watergate burglary. The scandal that toppled Nixon’s presidency began unraveling.

In the aftermath, a Senate committee investigated and confirmed the plot to poison Anderson. Liddy and Hunt eventually acknowledged their participation in the conspiracy. Colson never did. All three went to prison for Watergate-related crimes.

But not Nixon, whose role in the Anderson plot has never been definitively established. Hunt believed that Colson didn’t have the “balls” to order the assassination on his own and had acted at Nixon’s behest. Colson denied that. But it is hard to imagine Nixon’s closest advisers plotting to execute America’s leading investigative reporter without the tacit — if not explicit — authorization of the president.

Although the White House plot to murder a journalist was ultimately aborted, the outcome could easily have been very different — with nobody but the conspirators ever knowing what really happened.

Mark Feldstein, a journalism historian at the University of Maryland, is the author of “Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington’s Scandal Culture.” He worked as a student intern for Anderson in the summers of 1973 and 1976.

Source : Washington Post