The Trouble with FFELP ABS: An Explainer

By Timothy Bernstein, Analyst

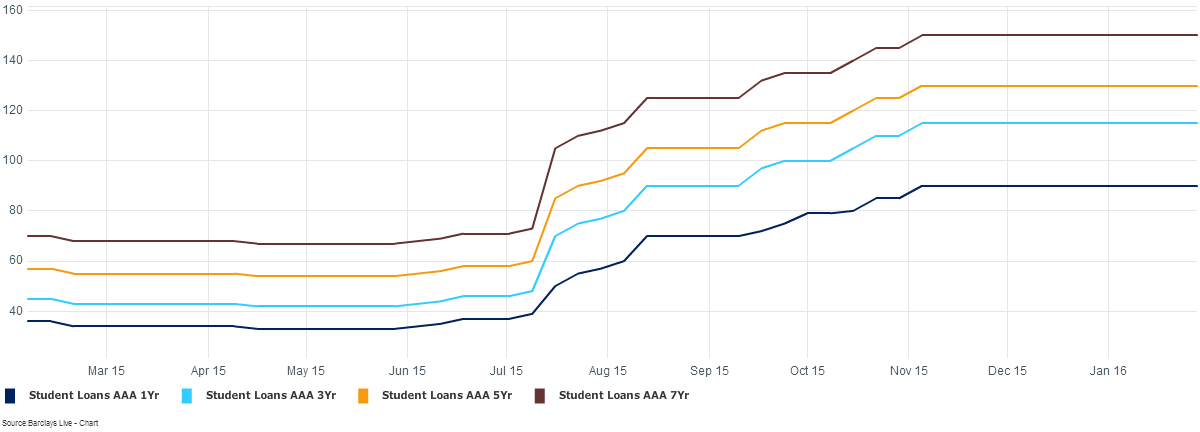

Since last summer, the student loan sector has been in a state of turmoil not seen since the financial crisis. While Moody’s and Fitch revisit their respective rating methodologies for federally-insured student loan asset-backed securities (FFELP ABS), yield spreads have skyrocketed. Since July of 2015, spreads have more than doubled and have now reached levels not seen since the post-crisis years of 2009 and 2010. While the market anxiously awaits a revised rating framework, it seems worth investigating what caused this climate of insecurity in the first place.

What is a FFELP Student Loan?

Simply put, a FFELP Student Loan is a loan that was made under the Federal Family Education Loan Program, a federal government initiative (since discontinued) through which private lenders made loans to students. Those loans were then insured by guaranty agencies and subsequently reinsured by the federal government for a minimum of 97% of the defaulted principal and accrued interest.

This level of implied protection has typically made FFELP ABS one of the lower-risk members of the Consumer ABS category. Despite its relatively low level of risk, FFELP ABS spreads have steadily widened since July of last year as Figure 1 indicates:

What caused the perceived increase in risk?

So far, it hasn’t really come from rising default rates. According to the Department of Education, 2015 saw a decrease in defaults across all sectors of the student loan market. Given that the fundamental credit risk of these securities has not changed, the spread widening instead seems to originate with the uncertainty around credit rating methodology. In July, just weeks after it placed a large number of tranches of FFELP ABS under review for downgrade, Moody’s announced a proposal to change the way it rated FFELP securitizations (Note – the spread jump in Figure 1 occurs on July 9th, the day Moody’s announcement came out). In November, Fitch followed suit with proposed amendments of its own. Since then, it has also placed a large number of tranches under downgrade review.

Why did the agencies propose these changes?

That’s a great question. While there are a number of contributing factors, the central concern at the heart of the proposals is that a significant number of FFELP ABS tranches will not fully pay down by their scheduled final maturity dates, a concern driven by the low payment rates (both repayment and prepayment) that the agencies are currently seeing.

Why are there such low repayment rates?

Again, there are a number of factors to consider, but the central reason (at least as cited by Moody’s and Fitch) is the substantial increase in the number of borrowers opting for extended repayment plans, the most widely available of which is the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plan that caps a borrowers’ payments based on their income and family size. These plans give borrowers much longer to repay their loans, with the maximum repayment period being 25 years (for comparison, the standard student loan term at issuance is around 10 years), after which the debt is forgiven[1] if the borrower still hasn’t paid it back, (subject to certain conditions).[2] This in turn would increase the weighted average life of a security backed by these newly-lengthened loans and thus create the possibility that senior tranches in a multi-class ABS structure may not fully repay by their legal maturity date.

There are other issues at play here as well. First, the number of loans in either deferment or forbearance (two different types of ways to postpone a loan repayment) remains high. Additionally, the pool balance in many deals now exceeds their original projections due to slower amortization and prepayment rates. Despite these additional concerns, the rating agencies seem most worried about extended repayment plans. Moody’s estimates that for certain FFELP securitizations, up to 10-15% of the collateral loans are either in IBR or something similar.

Do these concerns affect non-FFELP student loans?

As a matter of fact, they do; even if it isn’t clear that they should. Although Moody’s and Fitch have yet to make any noise about changing how they rate private SLABS, their professed concerns about the federal market inspire secondhand worry about student loans in general. Theresa O’Neill, an ABS Strategist at Bank of America Securities, acknowledged to GlobalCapital the “headline risk” that can weigh down an entire sector when “something totally unrelated to the private student loan sector gets picked up by the market.”

Where are we today?

We are in something of a holding pattern. The comment periods for both the Moody’s and Fitch revisions have ended and a number of FFELP tranches remain under consideration for downgrade. Neither agency has yet announced the changes they will make to their rating methods, or even when they will decide on those changes. In the meantime, spreads on FFELP ABS remain at their wides since the Moody’s press release, mostly on the uncertainty that still pervades the student loan sector.